A craving for ethanol-rich fruit has been discovered in black-handed spider monkeys in Panama, which may give insight into the evolutionary origins of humans’ liquor addiction. The animals’ alcoholic inclinations may corroborate the so-called “drunken monkey” hypothesis, which claims that our love of alcohol stems from our primate ancestors’ feeding habits, according to a recent study published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

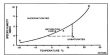

The drunken monkey theory was first presented by biologist Robert Dudley of the University of California, Berkeley, and is based on the assumption that fruit-eating animals benefit from slightly overripe fruit due to its greater sugar content and calorific value. However, as these sugars ferment, ethanol is produced, suggesting that these animals may have evolved to consume alcoholic beverages.

While non-human primates have been observed eating ethanol-rich fruit, scientists have never determined if they had the ability to metabolize alcohol in order to obtain its calories. Dudley and his colleagues went to Panama’s Barro Colorado Island to explore, where indigenous spider monkeys spend much of their time eating the sweet fruit of the local jobs’ tree. The researchers discovered that the pulp of half-eaten fruit dropped by foraging monkeys had an average of 1 to 2 percent ethanol, showing that the animals have a predilection for alcoholic food.

“We have been able to establish, without a doubt, that wild monkeys ingest fruit-containing ethanol without human involvement for the first time,” research author Dr. Christina Campbell said in a statement. “The monkeys were probably consuming the ethanol-laced fruit for the calories,” she explained. “Fermented fruit would provide them with more calories than unfermented fruit. The bigger the calorie count, the more energy you’ll have.”

Six foraging spider monkeys’ urine samples were also obtained, and secondary metabolites of alcohol intake were found in five of them. This demonstrates that the animals are capable of digesting alcohol and gaining access to its calories. “This is just one research; more must be done,” Campbell remarked. “However, it appears that the ‘drunken monkey’ idea – that humans’ predisposition to consume alcohol derives from a deep-rooted preference of frugivorous (fruit-eating) monkeys for naturally-occurring ethanol within ripe fruit – may have some validity to it.”

While Dudley claims that the amount of alcohol ingested by Panamanian monkeys is insufficient to get them intoxicated, the authors speculate that “human ancestors may have preferentially picked ethanol-laden fruit for eating” owing to its high-calorie content. To put it another way, our fondness for alcohol may derive from our evolution as fruit-eating monkeys seeking fermenting carbohydrates.

“These ancestral links between ethanol and nutritional reward may, in turn, originate from contemporary patterns of alcohol intake,” the researchers write. While our natural predilection for alcohol suited us well when ripe fruit was our only poison, the current abundance of inebriants has transformed us all into drunken monkeys, turning our evolved choices into a significant public health hazard. From this vantage point, the authors conclude that “excessive alcohol intake, like diabetes and obesity, may be understood conceptually as an illness of nutritional excess.”