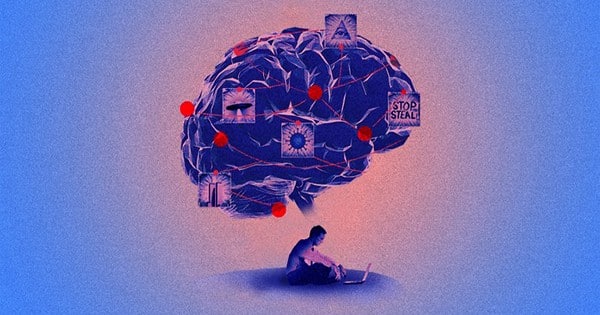

From the traditional Flat Earth movement to QAnon “truthers” and anti-vaccine zealots, you don’t have to travel far in our interconnected world to find someone peddling conspiracy theories. Friends and relatives are sometimes surprised when someone falls down the rabbit hole into the murky world of conspiracies – how does a previously sensible person become seduced into believing that dinosaurs do not exist? Well, psychology could well hold the answer.

Seeing patterns

A lot of scientific studies have been prompted by the desire to understand what motivates people to believe in conspiracies. One aspect of the human brain appears to hold a significant amount of responsibility; nevertheless, it is also something we could not function without.

The brain is predisposed to look for patterns. As humans have evolved, this has proven highly beneficial. It’s useful to know, for example, that the color red is frequently associated with “danger”. It’s less convenient to go from “Hmm, we appeared to have misplaced some ships,” to “It must be an eldritch triangle of ocean gobbling up vessels like there’s no tomorrow!”

“Our brain is continuously attempting to make sense of the external world. The problems begin when this pattern-recognizing power goes into overdrive, connecting dots in random data and adding two and two to make five. This idea is known as illusory perception.

A 2017 study published in the European Journal of Social Psychology investigated this further. The researchers led groups of up to 401 people through five tests aimed at investigating the link between conspiracist thinking and illusory pattern perception.

The study discovered a correlation between confidence in several prominent conspiracies, such as those involving climate change, the moon landing, and the assassination of JFK, and seeing a pattern in a series of random coin flips. Those with a more conspiratorial mindset were also more likely to recognize patterns in chaotic artwork, such as Jackson Pollock’s splatter paintings.

The researchers also investigated a typical discovery in conspiracy circles: belief in one crazy hypothesis is frequently predictive of belief in other, unrelated hypotheses. If you agree that Barack Obama is a reptile disguised as a human, it’s only a short step to believing that the US government was aware of 9/11 ahead of time.

“[A]cceptance of a conspiracy theory implies an increase in the extent to which people perceive patterns in world events, as reflected in the belief that instead of being a coincidence, many events that happen in the world are somehow causally related,” the study’s authors wrote.

To test this, they allowed participants to read either a pro- or anti-conspiracy article before answering questions on their perception of a pattern in world events, and they discovered a correlation in those who had been exposed to the conspiracy idea.

To summarize the study’s findings, the authors stated, “We conclude that illusory pattern perception is a central cognitive ingredient of beliefs in conspiracy theories and supernatural phenomena.”

Following the rise of conspiracy theories surrounding the COVID-19 epidemic, this research became even more pertinent, and subsequent investigations have expanded on the ideas presented here.

One from the height of the pandemic in 2020 emphasized the importance of illusory perception while also touching on the concept of confirmation bias.

“[Conspiracy theory] believers may find it hard to believe that a virus could originate randomly from the natural world because it does not fit with their preconceived view that events have a reason and usually a human or government influence behind it,” the paper’s authors wrote.

The Role of Personality

The role of personality has also emerged as a significant aspect in psychological investigations of conspiracy ideas.

Narcissism, or the conviction in one’s superiority over others, has been identified as one of the most reliable psychological predictors of a proclivity for conspiracy theories. A 2022 study identified three characteristics of narcissistic personalities that appear to support this: agentic extraversion (which includes traits such as aggressiveness, self-confidence, and reward-seeking), hostility, and neuroticism.

In a nutshell, narcissistic people are more likely to feel that others are “out to get them,” which means that conspiracy theories about evil government machinations or shadowy cabals dominating the media narrative fit right in with their style of thinking. Narcissists are also motivated by a desire to be unique, which has been linked to conspiratorial thinking in previous research.

Others may be driven to conspiracies because they want to “watch the world burn”; simply put, certain people live in turmoil.

Still, recent research has revealed a correlation between heightened anger and belief in conspiracies, while it is unclear whether anger is a cause or a result of irrational beliefs.

Some people may be drawn to conspiracies for the sake of entertainment. No doubt discussing the most ridiculous theories about our universe, whether or not you believe them to be true, may be entertaining. You clicked on this article, after all.

What We Know and What We Still Don’t

A systematic review published in 2022 sought to gather everything we know so far regarding conspiracy ideas as they relate to COVID-19, with insights that may be applied more generally.

Narcissism was mentioned again, together with the three other personality qualities that comprise the so-called Dark Tetrad (Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and sadism). Another reason identified was decreased psychological well-being, such as emotions of anxiety, depression, or uncertainty, which we presumably all remember from the first few months of 2020.

What is unclear is which factors are causes and which are consequences. Perhaps some people’s brains and dispositions predispose them to believe in conspiracies, but it takes a specific set of external conditions to push them over the brink and down the rabbit hole.

The review’s authors urged more studies to address these unresolved topics using more diverse samples. Above all, understanding the motivations that drive individuals to believe conspiracy theories – and remembering that these beliefs can have real-world repercussions – is critical if we are to confront future waves of disinformation head-on.